Farmers fear dingoes are eating their livestock – but predator poo tells an unexpected story

KILLING CARNIVORES to protect livestock, wildlife and people is an emotive and controversial issue that can cause community conflict. Difficult decisions about managing predators must be supported by strong scientific evidence. In Australia, predators such as dingoes (Canis lupus dingo) and foxes (Vulpus vulpus) are often shot or poisoned with baits to prevent them from killing sheep and cattle. Feral cats and foxes are also killed to protect native wildlife. But research elsewhere suggests public perceptions of how predators affect ecosystems and livestock are not always accurate. Our recent study sought to shed light on these controversies. We examined the scat, or poo, left behind by dingoes, foxes and cats. We focused on the Mallee region of Victoria and South Australia where there are calls to resume dingo culling to stop them killing livestock.

A contentious issue

Our study took place in the Big Desert-Wyperfeld-Ngarkat reserve complex in the semi-arid Mallee region of Victoria and South Australia. This continuous ecosystem comprises about 10,000sqkm of protected native mallee bushland, and is entirely surrounded by crop and livestock farming areas. Fox-baiting is conducted along the boundaries of Victorian-managed reserve areas. Dingo baiting occurs in the South Australian-managed section of the park. Since March 2024, the small dingo population has been protected in Victorian-managed areas due to their critically low numbers in the region. Prior to the change, Victorian farmers and authorised trappers could control dingoes on private land and within public land up to 3km from farms. Farmers say they have lost livestock since dingoes were protected.

What are predators eating in the Mallee region?

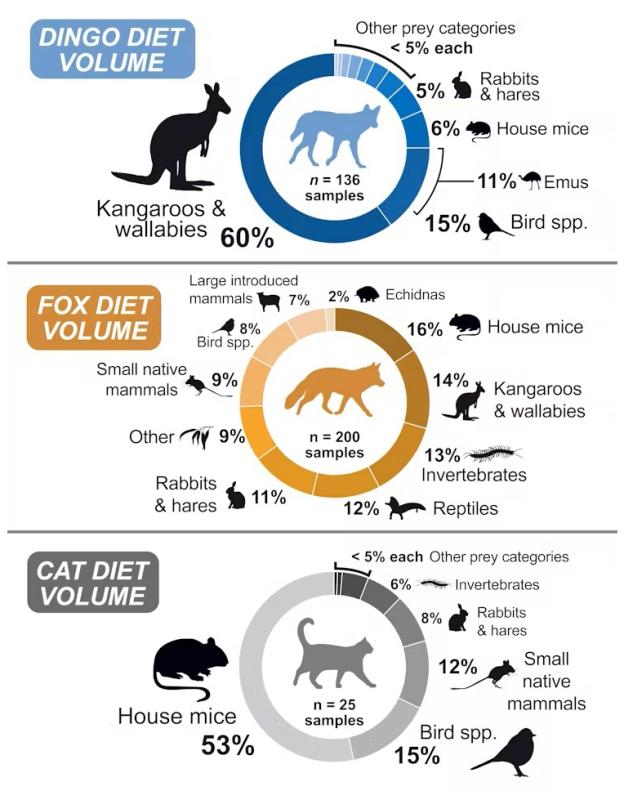

We collected and analysed 136 dingo, 200 fox and 25 cat scats to determine what each predator in the area was eating and how their diets differed.

Livestock was not a major part of the diet of dingoes, foxes or cats. Some 7% of fox scats contained sheep or cattle remains. This was more than that of dingoes, at 2% of scats. No feral cat scats contained livestock remains.

The dingo diet was dominated by kangaroos, wallabies and emus, which comprised more than 70% of their diet volume.

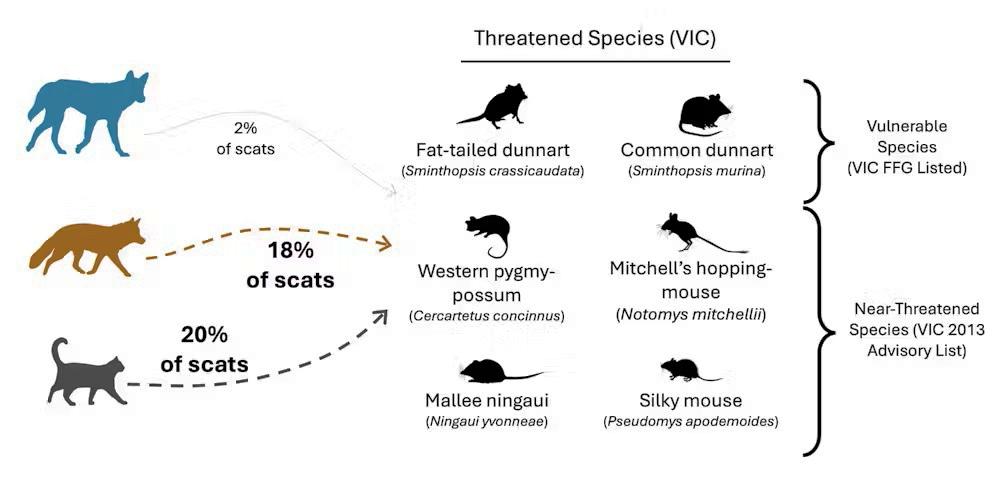

Cats and foxes consumed more than 15 times the volume of small native mammals compared with dingoes, including threatened species such as fat-tailed dunnarts (Sminthopsis crassicaudata).

Our data must be interpreted with caution. Scat analysis cannot differentiate between livestock killed by predators and those that are scavenged. It also can’t tell us about animals that a predator killed but did not eat.

In 2022–23, when we collected the scats, rainfall in the area was high and prey was abundant. So, while we found livestock were not likely to be a substantial part of these predators’ diets at the time of our research, this can change depending on environmental conditions.

For example, fire and extended drought may force predators to move further to find food and water. They may move from conservation areas to private land, where they could prey on livestock.

A taste for certain prey

A predator’s poo doesn’t tell the full story of how it affects prey populations.

To understand this further, we used motion-sensing wildlife cameras to assess which prey were available in the ecosystem. We compared it to the frequency they occurred in predator’s diets. This allowed us to determine if dingoes, foxes or cats target specific prey.

We found foxes and cats both consumed small mammals proportionally more than we expected, given the prey’s availability in the study area. Cats consumed birds at a higher rate than expected, and dingoes consumed echidnas (Tachyglossidae ) more than expected.

Further intensive monitoring work is needed to determine how these dietary preferences affect the populations of prey species.

Embracing the evidence

The findings build on a substantial previous research suggesting foxes and cats pose a significant threat to native mammals, birds, reptiles and other wildlife, including many threatened species.

Our results suggest foxes may cause more harm to sheep than dingoes overall – a finding consistent with research elsewhere in Victoria.

Dingoes were the only predator species that regularly preyed on kangaroos and wallabies. These species are abundant in the region. They can also compete with livestock for grazing pastures, consume crops and degrade native vegetation.

Currently, dingoes are killed on, or fenced out of, large parts of Australia due to their perceived threat to livestock.

Lethal control of invasive species remains important to protect native wildlife and agriculture. But such decisions should be based on evidence, to avoid unforeseen and undesirable results. For example, fox control can lead to increased feral cat numbers and harm to native prey. Fewer dingoes may mean more feral goats and kangaroos. Non-lethal and effective alternatives exist to indiscriminately killing predators to protect livestock, such as protection dogs and donkeys. These measures are being embraced by farmers and graziers globally, often with high and sustained success. In Australia, governments should better embrace and support evidence-based and effective approaches that allow farming, native carnivores and other wildlife to coexist.

About the authors

RACHEL MASON, PhD candidate in conservation biology, Deakin University. RACHEL MASON, PhD candidate in conservation biology, Deakin University.Rachel Mason conducted this research with grant funding from the Victorian Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action. She is a current member of the Australian Mammal Society, the Australasian Wildlife Management Society, and the Ecological Society of Australia. |

EUAN RITCHIE, professor in wildlife ecology and conservation, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, Deakin University. EUAN RITCHIE, professor in wildlife ecology and conservation, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, Deakin University.Euan Ritchie receives funding from the Australian Research Council and the Department of Energy, Environment, and Climate Action. Euan is a councillor within the Biodiversity Council, a member of the Ecological Society of Australia and the Australian Mammal Society, and president of the Australian Mammal Society. |

This article was first published in The Conversation on May 12, 2025. It is republished in Wildlife Australia under a Creative Commons — Attribution/No derivatives licence.

The original article can be found here: theconversation.com/farmers-fear-dingoes-are-eatingtheir-livestock-but-predator-poo-tells-an-unexpected-story-254787

Deakin University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

#ends

- Hits: 90